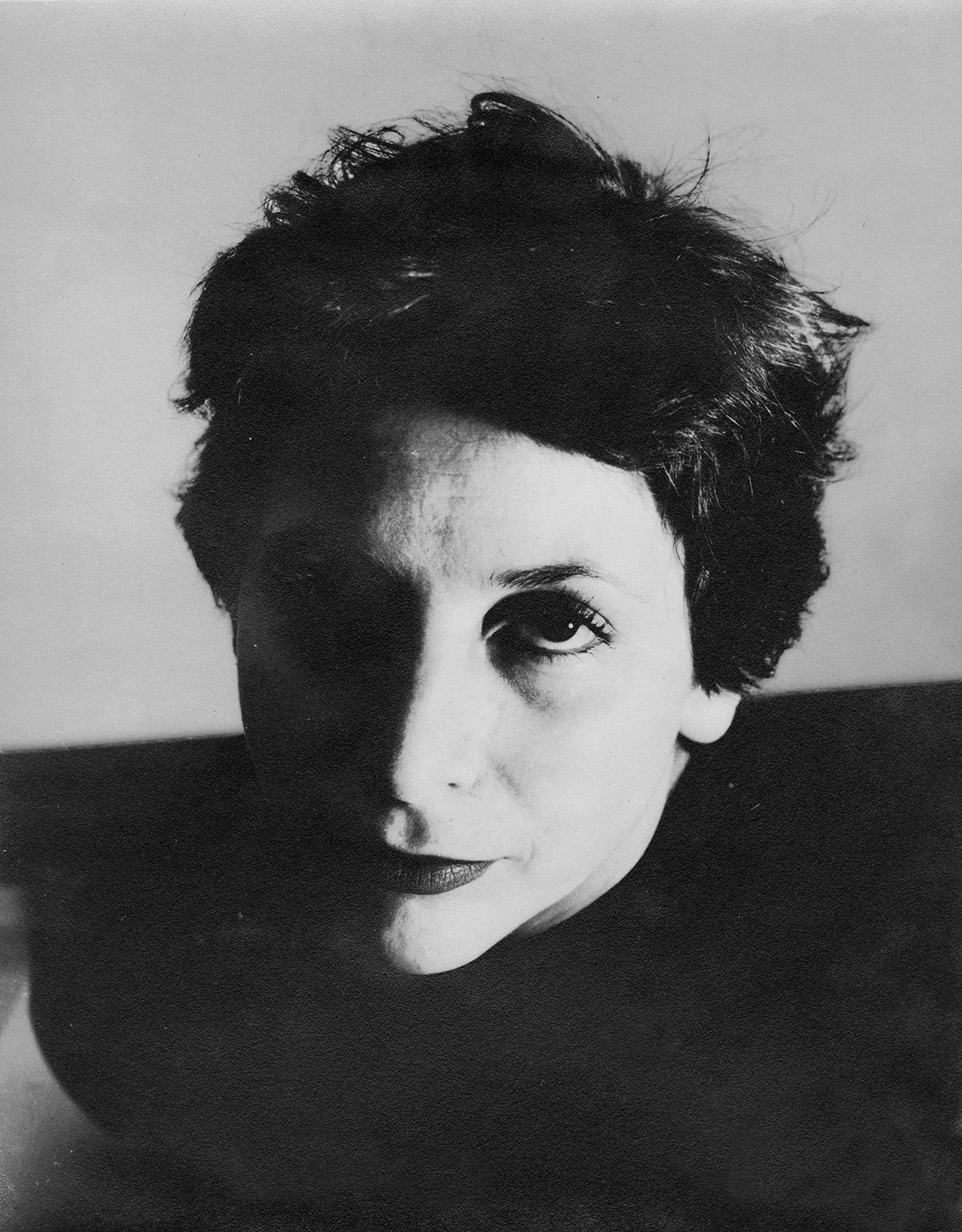

Nadia Gould

Nadia Gould is an under-recognized 20th-century artist, who worked primarily in New York City after fleeing Nazi occupied France as a teenager. Gould studied painting in the early 1950s, attending Fred Mitchell’s Southern Tip School of Art (Coenties Slip), where she developed a practice in geometric abstraction. During this time, she limited her visual vocabulary to the square, the triangle and the circle. An intuitive colorist, she created movement by manipulating shape – a disciplined approach that freed Gould to infinitely explore the confines of the picture plane. Her reliance upon her own hand, rather than mechanical tools, led to energetic and playful compositions and differentiated her from contemporary artists associated with Op Art.

Gould was notably included in the 1965 NY World’s Fair exhibition “Lesser Known and Unknown Painters,” alongside Robert Ryman, Robert Smithson, and Jamie Wyeth among other rising artists. She also participated with eminent contemporaries such as Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, and Lois Dodd in the Annual Graphics Show at Phoenix Gallery. These group exhibitions notwithstanding, Gould remained outside the mainstream, rejected classification with any movement, and throughout identified as self-taught.

In the early 1980s, Gould began to move away from geometric forms, introducing figurative subjects into her work. Having resided extensively in Central and South America, Asia, and Europe, Gould was inspired by ancient mythologies, indigenous religions, and art historical masterpieces. As her perspective turned outward, her work became more expansive. Her drawings from this period evolved into large acrylic paintings densely populated by figures, animals, and architectural references stacked upon each other in a shallow space. These sprawling and audacious murals set her naively drawn figures against discreet blocks of color, displaying Gould’s sharply honed command of composition. The result is a singular, colorful vision interweaving cultural references and the artist’s irreverent sensibility. Throughout, Gould’s work records a visual vocabulary uniquely her own, and a lifelong commitment to challenging viewer expectations.